Wallenberg Medal

Wallenberg Medal

The Wallenberg Medal of the University of Michigan is awarded to outstanding humanitarians whose actions on behalf of the defenseless and oppressed reflect the heroic commitment and sacrifice of Raoul Wallenberg, the Swedish diplomat who rescued tens of thousands of Jews in Budapest during the closing months of World War II.

| Sl | Name | Country | Flag | Year | Awarded For |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 30 | Nnimmo Bassey | Nigeria | 2024 | for outstanding defenseless humanitarians actions. | |

| 29 | Lucas Benitez | Mexico | 2023 | for outstanding defenseless humanitarians actions. | |

| 28 | Safa Al Ahmad | Soudi Arabia | 2019 | for outstanding defenseless humanitarians actions. | |

| 27 | March For Our Lives | United States | 2018 | for outstanding defenseless humanitarians actions. | |

| 26 | B.R.A.V.E. Youth Leaders | United States | 2018 | for outstanding defenseless humanitarians actions. | |

| 25 | Bryan Stevenson | United States | 2016 | for outstanding defenseless humanitarians actions. | |

| 24 | Masha Gessen | Russia | 2015 | for outstanding defenseless humanitarians actions. | |

| 23 | Ágnes Heller | Hungary | 2014 | for outstanding defenseless humanitarians actions. | |

| 22 | Maria Gunnoe | United States | 2012 | for outstanding defenseless humanitarians actions. | |

| 21 | Aung San Suu Kyi | Myanmar | 2011 | for outstanding defenseless humanitarians actions. | |

| 20 | Denis Mukwege | Rwanda | 2010 | for outstanding defenseless humanitarians actions. | |

| 19 | Lydia Cacho | Mexico | 2009 | for outstanding defenseless humanitarians actions. | |

| 18 | Desmond Tutu | South Africa | 2008 | for outstanding defenseless humanitarians actions. | |

| 17 | Sompop Jantraka | Thailand | 2008 | for outstanding defenseless humanitarians actions. | |

| 16 | Luise Radlmeier | United States | 2006 | for outstanding defenseless humanitarians actions. | |

| 15 | Paul Rusesabagina | Rwanda | 2005 | for outstanding defenseless humanitarians actions. | |

| 14 | Heinz Drossel | Germany | 2004 | for outstanding defenseless humanitarians actions. | |

| 13 | Bill Basch | Russia | 2003 | for outstanding defenseless humanitarians actions. | |

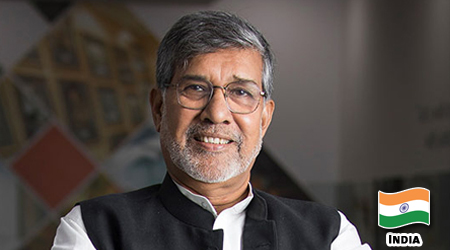

| 12 | Kailash Satyarthi | India | 2002 | for outstanding defenseless humanitarians actions. | |

| 11 | Marcel Marceau | France | 2001 | for outstanding defenseless humanitarians actions. | |

| 10 | Nina Lagergren | Sweden | 2000 | for outstanding defenseless humanitarians actions. | |

| 9 | John Lewis | United States | 1999 | for outstanding defenseless humanitarians actions. | |

| 8 | Simcha Rotem | Poland | 1997 | for outstanding defenseless humanitarians actions. | |

| 7 | Marion Pritchard | Netherlands | 1996 | for outstanding defenseless humanitarians actions. | |

| 6 | Per Anger | Sweden | 1995 | for outstanding defenseless humanitarians actions. | |

| 5 | Miep Gies | Austria | 1994 | for outstanding defenseless humanitarians actions. | |

| 4 | Tenzin Gyatso | China | 1994 | for outstanding defenseless humanitarians actions. | |

| 3 | Helen Suzman | South Africa | 1992 | for outstanding defenseless humanitarians actions. | |

| 2 | Jan Karski | Poland | 1991 | for outstanding defenseless humanitarians actions. | |

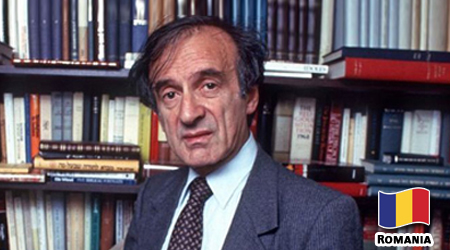

| 1 | Elie Wiesel | Romania | 1990 | for outstanding defenseless humanitarians actions. |

Wallenberg Medal Laureates (2025 ~ 2021)

Nnimmo Bassey

Wallenberg Medal 2024

“As an architect, poet, writer, and human rights advocate, Nnimmo Bassey works to address root cause issues driving climate migration, environmental and social impacts of extractive production, and hunger in the Niger Delta. His commitment to socio-ecological justice connects large-scale issues of climate change, exploitation of natural resources, and political/corporate intransigence to the lives of individuals in the Niger Delta and beyond,” said Sioban Harlow, Professor Emerita of Epidemiology and Global Public Health and chair of the Wallenberg Medal Executive Committee. “Just as Raoul Wallenberg trained as an architect at the University of Michigan before bringing his multifaceted skills to humanitarian work, Bassey’s background as an architect undergirds his environmental leadership.”

Lucas Benitez

Wallenberg Medal 2023

“Lucas Benitez’s work with the CIW reflects the ongoing need for frontline advocates for vulnerable people in our society. This movement harnesses the economic influence of consumers to improve working conditions, labor practices, and pay for farmworkers through its worker-led, market-enforced approach to the protection of human rights underlying corporate supply chains,” said Sioban Harlow, Professor Emerita of Epidemiology and Global Public Health and chair of the Wallenberg Medal Selection Committee.

View More

Wallenberg Medal Laureates (2020 ~ 2011)

Safa Al Ahmad

Wallenberg Medal 2019

“Safa Al Ahmad shows how journalism can give a voice to persons who are voiceless and give witness to events that escape the world’s notice,” said John Godfrey, chair of the Wallenberg Committee. “She embodies the courage and commitment to human rights and human dignity that the Wallenberg Medal recognizes.”

March For Our Lives

Wallenberg Medal 2018

“The students of March For Our Lives and B.R.A.V.E. have, with outraged insistence, demanded action to end gun violence in schools and communities across the country,” said John Godfrey, chair of the Wallenberg Committee. “They have disturbed the conscience of Americans in pushing to find a solution to this national crisis. This personal and tireless commitment embodies that of Raoul Wallenberg and represents everything this medal stands for.”

B.R.A.V.E. Youth Leaders

Wallenberg Medal 2018

“The students of March For Our Lives and B.R.A.V.E. have, with outraged insistence, demanded action to end gun violence in schools and communities across the country,” said John Godfrey, chair of the Wallenberg Committee. “They have disturbed the conscience of Americans in pushing to find a solution to this national crisis. This personal and tireless commitment embodies that of Raoul Wallenberg and represents everything this medal stands for.”

View More

Bryan Stevenson

Wallenberg Medal 2016

On the evening of March 7th, 2017, the 25th Wallenberg Medal, the most distinguished award given by the University of Michigan, was presented to civil rights lawyer and social rights activist Bryan Stevenson, who founded the Equal Justice Initiative, a non-profit organization working to guarantee a legal defense to every inmate on death row in Alabama, in 1989.

Masha Gessen

Wallenberg Medal 2015

On Tuesday President Mark Schlissel awarded the Wallenberg Medal to Masha Gessen, Russian American author, journalist and activist. The University’s most distinguished award, the medal commemorates Raoul Wallenberg, Michigan Class of 1935, whose actions in Budapest, Hungary during World War II saved the lives of tens of thousands of Jews. In presenting the Medal, President Schlissel said that “the lives he saved, and the generations he inspires, are strong reminders of one our most closely held values: that one person can make a difference. Wallenberg’s legacy as it lives on today makes me very proud to be part of the Michigan community.”Gessen is a prominent journalist whose work appears regularly in The New York Times, The New Yorker, and many other publications, and whose writing includes books about Putin’s Russia, the protests of Pussy Riot, a Russian feminist art collective, and the background story of the Tsarnaev brothers who were responsible for the Boston marathon bombings. A courageous and outspoken critic of the re-imposition of totalitarian structures in Russia and a strong advocate for LGBTQ rights, Gessen, her partner and their family were forced into exile two years ago and now live in New York.Gessen first learned about Wallenberg from her mother. “The first time I read about Raoul Wallenberg, I read a phrase that I have remembered for the rest of my life. ‘This is a man who tried to save the world and whom the world failed to save.’ The phrase was written by my mother. She was a journalist and literary critic who was probably the first person to write about Raoul Wallenberg in Russia. Today, I want to actually focus not on the part where one person can make a difference, but on the part where the world failed to save him. Today I want to talk about the victims.”She spoke of the dangers of misunderstanding the regime that Vladimir Putin has installed and the suffocation of public space and public opinion in Russia. “There are a lot of people in Russia who are in actual danger. I’m in a luxurious position because I live here. There are people doing work on the ground in Russia that you’ve never heard of. There are people who take such great risks every day and we don’t even know about them.”Gessen concluded the evening by telling how she first encountered Ann Arbor during the Soviet era as two words printed on the spine of books that constituted the “lost literature” of twentieth-century Russia—fiction and poetry that had been repressed in the Soviet Union but were reproduced in Ann Arbor by Carl and Ellendea Proffer, scholars of Russian literature, and clandestinely re-introduced to Russia. “When growing up, they were the best books in the house. They had a little horse carriage as a logo and the words ‘Ann Arbor’ underneath, which I thought was some magical place where the best books came from. The words ‘Ann Arbor’ continued to have this magical ring to me, and I have never been able to come here until now.”

Ágnes Heller

Wallenberg Medal 2014

On September 30, the 2014 Wallenberg Medal is being awarded to Agnes Heller, a distinguished philosopher and Holocaust survivor who seeks to understand the nature of ethics and morality in the modern world, and the social and political systems and institutions within which evil can flourish.Like Wallenberg, Professor Heller has demonstrated that courage is the highest expression of civic spirit. She has been witness to regimes that have organized murder, crushed dissent and persecuted independent voices. In 1944, as a young woman surviving in Budapest, she knew the name Wallenberg. She spoke out vigorously for autonomy and self-determination after the suppression of the Hungarian Revolution of 1956. Following the defeat of the 1968 Prague Spring, she went into exile and became the Hannah Arendt Visiting Professor of Philosophy in the Graduate Studies Program of The New School in New York. She is a highly influential scholar who publishes internationally-acclaimed work on ethics, aesthetics, modernity, and political theory. In 2010, she was awarded Germany’s Goethe Medal. Since retirement, Agnes Heller has returned to Budapest. She remains fully engaged in public life, speaking out against the neo-nationalist and anti-Semitic strains again current in Hungary.She will be awarded the medal and will present the Wallenberg Lecture on September 30, 2014 at 7:30 at the Rackham Graduate School. The Wallenberg Lecture is open seating, no tickets or reservations, first come first seated. Please save the date to join us!

Maria Gunnoe

Wallenberg Medal 2012

Maria Gunnoe is a fearless advocate for environmental and social justice. Despite threats and intimidation Ms. Gunnoe works to educate and build citizen advocacy, and to rally communities that face the destruction of their natural environment in her home of Boone County, West Virginia.

Aung San Suu Kyi

Wallenberg Medal 2011

Nobel Peace laureate Aung San Suu Kyi has committed her life to the non-violent struggle for democracy and human rights in Burma. Since 1988, she has been the leader of the democratic opposition and a voice of conciliation and unity among the regions and peoples of Burma.

Wallenberg Medal Laureates (2010 ~ 2001)

Lydia Cacho

Wallenberg Medal 2009

Lydia Cacho is a journalist, author, feminist and human rights activist. She has spoken out against the abuse of women in Mexico, using the unsolved murders in Ciudad Juárez as a call to action against the failure to bring justice to perpetrators of violence against women. Cacho founded Ciam Cancún, a shelter for battered women and children, providing refuge for countless individuals.Lydia Cacho was born in Mexico City in 1963 to a Mexican father and a French mother. She settled in Cancún, Mexico in 1985, where she began working at the newspaper Novedades de Cancún. She has published hundreds of articles, a book of poetry, a novel, several books of essays on human rights and other nonfiction works. She speaks Spanish, French, Portuguese and English.A fearless and courageous defender of the rights of women and children in Mexico, Cacho routinely risks her life to shelter women from abuse and challenge powerful government and business leaders who profit from child prostitution and pornography. Cacho is the founder of Ciam Cancún, a shelter for battered women and children. Her work with women and children in Mexico has been extremely effective in terms of rescue and rehabilitation of the countless individuals who seek assistance from the shelter. She has spoken out against the abuse of women in Mexico, citing the unsolved murders in Ciudad Juárez as a call to action against the failure to bring justice to perpetrators of violence against women. Journalist Marianne Pearl has described Cacho as “a woman of great strength and courage…who is deeply committed to ethical journalism and the advancement of human rights in Mexico for the long haul.”Her writings have resulted in shining the spotlight on issues that are normally not challenged. In her 2005 book, Los Demonios del Edén (Demons of Eden), Cacho accused a prominent businessman of protecting a child pornographer, which resulted in her illegal arrest. While in jail she was beaten and abused. She became the first woman to bring a case to the Mexican Supreme Court; the court ruled that the content of her book was truthful.Confronted with countless credible threats against her life, Cacho has refused offers of asylum from the United States, France and Spain. She will not leave her country and abandon the women and children she has dedicated her life to protecting. An April 2007 Washington Post article described Cacho as “one of Mexico’s most celebrated and imperiled journalists.” The article went on to explain that she “is a target in a country where at least seventeen journalists have been killed in the past five years and that trailed only Iraq in media deaths during 2006. Do-gooders and victims want to meet her, want to share their stories. Bad guys—well, they want her in a coffin.” Dead or alive, Lydia is committed to changing Mexico so that impunity for gross human rights violations will not be a part of the norm in her country.Cacho has received many awards for her work as a humanitarian and a journalist, including the State Journalists Prize in 2000, the Amnesty International Ginetta Sagan Award for Women and Children’s Rights in 200, and the UNESCO/Guillermo Cano Freedom of Expression Award in 2008. The Ginetta Sagan Amnesty International Award committee said of her: “It is also worth mentioning that her work has made her highly visible. Despite the many achievements and accolades that come with such recognition, Lydia remains deeply humbled and genuine. She is rooted in her community and no amount of recognition will ever change this. We have seen this firsthand.”

Desmond Tutu

Wallenberg Medal 2008

The first black South African Anglican Archbishop of Cape Town, Archbishop Desmond Tutu rose to international fame during the 1980s as a deeply committed advocate of nonviolent resistance to apartheid. In 1995, Nelson Mandela asked Tutu to investigate atrocities committed on all sides during the apartheid years, appointing him chair of South Africa’s Truth and Reconciliation Commission.Desmond Mpilo Tutu was born in Klerksdorp, South Africa on October 7,1931. His father was a schoolteacher, his mother a domestic worker.After three years as a high school teacher, in 1958 he entered the Anglican ministry. He received his Licentiate in Theology in 1960 from St. Peter’s Theological College, Johannesburg, and was ordained to the priesthood in Johannesburg in 1961. Not long after his ordination, Tutu obtained his Bachelor of Divinity Honors and Master of Theology degrees from King’s College, University of London, England.From 1967 to 1978 he served in a number of increasingly prominent positions, from lecturer at the Federal Theological Seminary at Alice, South Africa and chaplain at the University of Fort Hare; to lecturer in the Department of Theology at the University of Botswana, Lesotho and Swaziland; to an appointment as Associate Director of the Theological Education Fund of the World Council of Churches, in Kent, United Kingdom; to Dean of St. Mary’s Cathedral, Johannesburg; and finally Bishop of Lesotho.By 1978, in the wake of the 1976 Soweto uprising, South Africa was in turmoil, and Bishop Tutu was persuaded to take up the post of General Secretary of the South African Council of Churches (SACC). It was in this position that he became both a national and international figure. Justice and reconciliation and an end to apartheid were the SACC’s priorities, and as General Secretary, Bishop Tutu pursued these goals with vigor and commitment. Under his guidance, the SACC became an important institution in South African spiritual and political life, challenging white society and the government and affording assistance to the victims of apartheid.Inevitably, Bishop Tutu became heavily embroiled in controversy as he spoke out against the injustices of the apartheid system. For several years he was denied a passport to travel abroad. He became a prominent leader in the crusade for justice and racial conciliation in South Africa. In 1984 he received a Nobel Peace Prize in recognition of his extraordinary contributions to that cause. In 1985 he was elected Bishop of Johannesburg.In 1986 Bishop Tutu was elevated to Archbishop of Cape Town, and in this capacity he did much to bridge the chasm between black and white Anglicans in South Africa. And as Archbishop, Tutu became a principal mediator and conciliator in the transition to democracy in South Africa.In 1995 President Nelson Mandela appointed him Chairman of the Truth and Reconciliation Commission, a body set up to probe gross human rights violations that occurred under apartheid.In 1996, shortly after his retirement from office as Archbishop of Cape Town, Tutu was granted the honorary title of Archbishop Emeritus.Archbishop Tutu has held several distinguished academic and world leadership posts. He was elected Fellow of Kings College; President of the All Africa Conference of Churches, London; Chancellor of the University of the Western Cape, the William R. Cannon Professor of Theology at the Candler School of Theology, Emory University, Atlanta; Visiting Professor at the Episcopal Divinity School, Cambridge, Massachusetts; Visiting Scholar in Residence at the University of North Florida, Jacksonville; and Visiting Professor of Post-Conflict Studies at Kings College.In recent years Tutu has turned his attention to a different cause: the campaign against HIV/AIDS. The Archbishop has made appearances around the globe to help raise awareness of the disease and its tragic consequences in human lives and suffering.Archbishop Tutu holds honorary degrees from over one hundred and thirty universities, including Harvard, Oxford, Cambridge, Columbia, Yale, Emory, the Ruhr, Kent, Aberdeen, Sydney, Fribourg (Switzerland), Cape Town, Witwatersrand and the University of South Africa.He has received many prizes and awards in addition to the Nobel Peace Prize, most notably the Order for Meritorious Service Award (Gold) presented by President Mandela; the Archbishop of Canterbury’s Award for Outstanding Service to the Anglican Communion; the Prix d’Athene (Onassis Foundation); the Family of Man Gold Medal Award; the Mexican Order of the Aztec Medal (Insignia Grade); the Martin Luther King Jr. Non-Violent Peace Prize; the Sydney Peace Prize and the Gandhi Peace Prize.His writings include No Future Without Forgiveness and God Has a Dream.Though his vigorous advocacy of social justice once rendered him a controversial figure, today Archbishop Tutu is regarded as an elder world statesman with a major role to play in reconciliation, and as a leading moral voice. He has become an icon of hope far beyond the Church and Southern Africa.

View More

Sompop Jantraka

Wallenberg Medal 2008

Sompop Jantraka established an organization in Thailand to rescue girls and young women from sexual trafficking in Thailand and the neighboring region of southeast Asia. His work has offered shelter, education and a future for thousands of children and disrupted networks that exploit the poor and vulnerable.

Luise Radlmeier

Wallenberg Medal 2006

Sister Luise Radlmeier came to the attention of the Wallenberg Committee through an article in Reform Judaism (Fall 2005) which reveals how Congregation Har HaShem in Boulder, Colorado organized the sponsorship for ten young Sudanese women in Colorado through the efforts of this Dominican missionary. Sr. Luise has served her order in many ways — some of them unexpected and unplanned by her order.Luise Radlmeier was born in Pfeffenhausen, Bavaria in 1937. She recognized her vocation early in life and joined the Dominicans in 1956.At the age of 19 she was sent to Africa, where she served the Dominicans in a number of countries, including Zimbabwe, Zambia and Kenya. In the course of this she also received a university education, including a Master’s degree from the Sorbonne while on scholarship, and later became a lecturer in Religious Studies.In 1985 she was sent to Nairobi, Kenya. Her assignment was to lecture at a local college and contribute to the support of the other Sisters. It was in 1987 that she began her personal mission of assisting the children of war-torn Sudan. This started in an informal and part-time fashion. There were ever-increasing numbers of Sudanese refugee children coming to the house to beg the Dominican Sisters for sustenance. Sr. Luise responded by helping them to find not only food and housing: her goal was to provide them with an education. This was not a routine part of the Sisters’ mission but was certainly in keeping with Dominican values.Initially, she placed 27 of the refugee children in a number of area schools and paid for their primary schooling and for secondary education in trades and technical fields that would make them self-reliant. By 1990 she moved her efforts to a larger scale, continuing to enroll the ever-increasing numbers of refugee children who, despite the incredible challenges, were making their way to Nairobi from the camp in Kakuma (run by the United Nations) more that 700 kilometers away. Sr. Luise raised the funds to enroll hundreds of Sudanese children in primary and secondary schools – promising them a future through carpentry, mechanics, plumbing, computer and secretarial skills. When sufficient funds were available she supported the schooling of as many as 800 children a year.By the late 1990s Sr. Luise was involved in many ways in efforts to aid this lost generation of Sudanese youth. As she continued to support and educate hundreds of the refugees who make their way to her in Nairobi she expanded her efforts. For example, Sr. Luise works through the Joint Voluntary Agency to assist with the preliminary interviews that determine resettlement. She helped to settle many of the Lost Boys of Sudan from the camp at Kakuma by preparing them for the tests they would have to take to immigrate to the USA, Canada and Australia.In 2002, Sr. Luise finally left her position as a lecturer in the college to attend full time to the needs of the refugees and orphans. During the course of the 1990s she was able to secure funding from a wide range of private and public sources and gradually built a compound in Juja, some 48 kilometers northeast of Nairobi. There she established dormitories for students, a home for AIDS Orphans and HIV positive children, a clinic, two nursery schools and a primary school. She also established a modest hospital in nearby Thika. This is for the local poor and destitute but benefits the refugees, too.In 2005 the peace talks between warring factions in Sudan resulted in major NGOs shifting their policies. Now they provide funding for education only to groups inside Sudan and not in neighboring countries where most of the refugees are. However, there is no shortage of children and adolescents who come to Sr. Luise for help, nor has she lost her desire to secure a future for Sudanese youth in the refugee camps.She continues to care for refugees from throughout east Africa, though the majority are Sudanese. The focus of her activity remains education and health care. In Juja her efforts support an AIDS Orphanage which is home to 132 Kenyan children; 137 other orphans are placed with “grandmothers” in surrounding villages. At the hospital Sudanese are treated for free but Kenyans must pay. (A German Parish in Nurnberg supports the hospital and orphanage, with plans for extended services.)In late 2005 she was paying for the education of 75 children in vocational school, 135 children in secondary school, and 100 children in primary school—all refugees. Funding cuts do mean that new admissions are fewer than half of what they used to be. Besides those at Juja, she has been trying to support the education of 166 secondary pupils and 67 vocational trainees in schools around the region. She has had some 200 applications from former child soldiers for money for vocational training which she cannot provide at this time. Another 40 had been accepted but must wait for their vocational training because there is no money.Currently, funding comes from small charitable organizations and informal, personal sources. For example Sr. Luise receives donations from Caritas Austria, the Christian Foundation for Children and the Aging in Kansas and Jewish organizations in Colorado; from her home parish in Germany; from the sale of clothes made by the young women under her care. She raises money wherever and however she can.Sr. Luise’s dream now is to bring 300 or more girls out of the camp at Kakuma where they daily face abuse and exploitation with no promise of a future. Her plan is to provide these girls with an education in Nairobi and eventually secure their resettlement, as happened with the Lost Boys of Sudan.

Paul Rusesabagina

Wallenberg Medal 2005

In 1994 the country of Rwanda descended into madness. In the spring of that year tensions were high due to years of political and economic strife. When President Juvenal Habyarimana died after his plane was shot down on April 6, this ignited longstanding conflict between two ethnic groups, the Hutu and Tutsi. Encouraged by the presidential guard and radio propaganda, an unofficial militia group called the Interahamwe was mobilized. These extremist Hutus began to slaughter the Tutsi population as well as some moderate Hutus. Over the course of 100 days, almost one million people were killed.In the face of this genocide, one man made a promise to protect the family he loved and in the course of doing his job found the courage to save over 1,200 people. Paul Rusesabagina used his influence and connections as temporary manager of the Hotel des Mille Collines to shelter over 1,200 Tutsis and moderate Hutus from being murdered by the Interahamwe militia. Who is this extraordinary man? “I don’t consider myself a hero. I consider myself as a normal person who did what he had to do, who has done his job.”His personal history is typical of a man who was serious about his studies and about pursuing a career. Rusesabagina was born June 15, 1954, at Murama-Gitarama in the Central-South of Rwanda; his parents were farmers. He attended primary and secondary school at the Seventh Day Adventist College of Gitwe, then the Faculty of Theology in Cameroon. In 1979, Rusesabagina found work at Sabena’s newly opened hotel in the Akagera National Park. This experience prompted him to enroll in the hotel management program at Utalii College in Nairobi, Kenya, which included time in Switzerland. Rusesabagina joined Sabena Hotels again and was employed at the Hotel des Mille Collines until November 1993, at which time he was promoted to general manager of the Hotel des Diplomates, also in Kigali.When the violence began April 6, Rusesabagina brought his family back to the Hotel des Mille Collines for safety. Though Rusesabagina is a Hutu, and so was safe from the Interahamwe, his wife Tatiana is a Tutsi. He could not escape the war zone with his family without outside help. Theirs was not the only family seeking refuge in the hotel. Beginning on April 7, hundreds of people — most of them Tutsi or Hutu threatened by Interahamwe supporters — took shelter at this luxury hotel in central Kigali owned by Sabena Airlines. Although set apart from city streets by its spacious, well-groomed grounds, the hotel offered no defense against attack beyond its international connections.Rusesabagina recognized the value of those connections. On April 15, acting as temporary manager of the hotel, he called for its protection in an interview with a Belgian newspaper. So, too, did an official of Sabena, who spoke on Belgian television. Rwandan authorities responded by posting some National Police at the hotel. In later contacts with the press and others, by telephone calls and fax messages, occupants of the hotel made the Mille Collines a symbol of the fear and anguish suffered by the Tutsi and others during these weeks.On April 23, a young lieutenant of the Department of Military Intelligence arrived at the hotel at around 6 a.m. and ordered Rusesabagina to turn out everyone who had sought shelter there. Told that he had half an hour to comply with the order, Rusesabagina went up to the roof and saw that the building was surrounded by military and the Interahamwe. He and several of the occupants began telephoning influential people abroad, appealing urgently for help. Rusesabagina explained, ”I only went on doing my job. Doing my work, my responsibility, my day to day duty.” One of the foreign authorities called from the hotel was the Director General of the French Foreign Ministry. Before the half hour had elapsed, a colonel from the National Police arrived to end the siege.In a similar incident on May 13, a captain came to the hotel in the morning to warn that there would be an attack at 4 p.m. On that day, the French Foreign Ministry received a fax from the hotel saying that Rwandan government forces plan to massacre all the occupants of the hotel in the next few hours. That French ministry directed its representative at the U.N. to inform the Secretariat of the threat and presumably also brought pressure to bear directly on authorities in Kigali, as others may have done also. The attack never took place.In fact, because of the bravery and leadership of Rusesabagina, none of the people who took shelter at the hotel was killed during the genocide. “I didn’t think about leaving, because all of the people who were in the Mille Collines, they only had hope in me. And leaving them down, it would have been a disaster. And as I told you, sometimes we have to face history.”That history is a shameful one for Rwanda and every other country that knew of the evil massacres. No foreign aid came from the United Nations or its more powerful Western member states until over 900,000 Rwandans had been murdered.Rusesabagina’s experience forced him to conclude: “The two words ‘never’ and ‘again’ are the most abused words in the world. In 1994 when the genocide was taking place in Rwanda, that is when they inaugurated the Holocaust Museum in Washington DC, and the two most repeated words where ‘never’ and ‘again’. And yet an average of 10,000 people were being butchered each and every day in a small tiny country and nobody cared about that. An African human life does not count in the west.”In September 1996 Rusesabagina and his family moved as refugees to Belgium where he now has his own business. He remains involved in charitable organizations aiding survivors of the Rwandan tragedy and has established a foundation in his name that provides assistance to children who survived the slaughter.

Heinz Drossel

Wallenberg Medal 2004

“I am no killer. I am a human being.”Heinz Drossel was a lieutenant in the German army during World War II who refused to join the Nazi Party and who protected Jews and helped them escape the Holocaust.Drossel, the son of ardent anti-Nazis, completed his education in law just before the war but was barred from joining the legal profession because he refused to join the Nazi party or its affiliated organizations. Instead, he was drafted into the army. While remaining steadfast in his opposition to the Nazis, he took part in the invasion of France in 1940 and then was sent to the Eastern Front to fight against the Soviet Union. He was commissioned as an officer in 1942.At great risk to his own life, Drossel acted on his convictions in the most extreme circumstances. In 1941, he released Russian prisoners to return to their own lines rather than execute them as he was directed. When his unit captured a Russian officer, Drossel quietly defied his commander’s order to take him back to headquarters where he knew the prisoner would be shot. Rather he turned the officer loose and directed him toward the Russian lines, telling him, “I am no killer. I am a human being.”On leave in Berlin in 1942 while recovering from illness, Drossel came across a young woman who, seeing him approach in his uniform, seemed increasingly agitated as he neared and poised to leap from the railing of a bridge into the river below. He stopped her from jumping and, while trying to calm her fear, learned that she was Jewish and was terrified that she would be discovered and sent to a concentration camp. Drossel took Marianne Hirschfeld to his family’s apartment, which had been empty since they had left Berlin for the little town of Senzig in the nearby countryside to escape the danger of the night-time bombing raids by the Allies. Risking his own life, he kept her secret and gave her money so she could find a safe place to stay before he returned to his unit.In 1945, while on leave to visit his parents at Senzig, a Nazi supporter in the community denounced friends who were Jewish and had been living quietly with forged identification papers. Jack and Lucie Hass, their daughter Margot, and her friend, Ernst Fontheim, faced imminent arrest and asked the Drossels for help. Heinz quickly took Jack Hass and Fontheim to the safety of the family apartment in Berlin, and found Margot and her mother shelter in another apartment. The Gestapo arrived in Senzig the next day to find no trace of them.Back on the Eastern Front in the waning days of the war, Drossel told his unit to open fire on an SS unit that had ordered them to attack Russian positions. Drossel was arrested and awaiting execution when he was freed by the Russian advance. After several months, Drossel was released from a Russian prison camp and went home. In the streets of a ruined Berlin he encountered Marianne Hirschfeld, who he had saved three years earlier. They were married in 1946. Heinz Drossel was able to take up his legal career. He became a judge, retiring in 1981.Ernst Fontheim moved to Ann Arbor with his wife Margot where he became a senior research scientist in the department of Atmospheric, Oceanic and Space Sciences at the University of Michigan.In 2001 the German government awarded Heinz Drossel its highest civilian medal and he was honored as one of the Righteous Among Nations by Yad Vashemwas honored as one of the “Righteous Among the Nations” by Yad Vashem, Israel’s memorial to Jewish victims of the Holocaust. He said, “After I got the honor of Yad Vashem, I have spoken before more than 5,000 German young people in schools and high schools. It’s necessary to give young people the courage to be human.” In 2013, Katarina Stegelmann published a biography of Heinz Drossel, Bleib immer ein Mensch: Heinz Drossel, ein stiller Held 1916-2006 (Berlin: Aufbau).

Bill Basch

Wallenberg Medal 2003

“In order to survive we must accept the responsibility of being our brothers’ and sisters’ keepers. Each one of us must do our share of improving our society one day at a time. We all have the ability to defeat evil in our own way.”-Bill BaschAs a young teenager in Budapest, Bill Basch worked as a courier for Raoul Wallenberg, delivering messages and distributing Schutz-Pässe to Jews in hiding.Bill Basch was born in 1927 in the small village of Szaszovo, in the Carpathian Mountains of eastern Czechoslovakia which today is part of western Ukraine. His father owned the largest store in the village. Bill grew up in a traditional Jewish household. He and his brothers attended Hebrew school at the small synagogue supported by the thirty-some Jewish families in the village.When the Germans transferred the Carpathian regions to Hungary in 1940, new anti-Semitic laws took root in the villages of the mountain slopes, threatening the sheltered world of home and synagogue. Jewish schools and businesses were closed. Bill’s father decided to send his three sons to different cities to increase their chances of survival.At the age of 15, Basch went alone to Budapest where he joined the resistance movement in a city filling with Jewish refugees fleeing other parts of Europe where the Nazis were implementing the Final Solution. But in 1944, the Germans occupied Hungary and began mass deportations of Jews to concentration camps in Germany and Poland. That same year, Raoul Wallenberg joined the Swedish legation in Budapest and Basch began working with Wallenberg’s network to deliver fabricated protection papers to Jews facing deportation. He negotiated the alleyways and the sewer system under Budapest’s streets to avoid patrols of German troops and their Hungarian militia sympathizers.Basch’s work with the underground came to an abrupt end in November 1944 when he mistakenly exited a sewer in a courtyard and encountered Hungarian fascist militiamen. A chase ensued and, to escape, Bill fell in with a group of people who, he discovered, were being marched to the train station for deportation to Buchenwald.At Buchenwald, Basch’s survival instincts endured. He volunteered for a crew repairing bombed railroad tracks, knowing that those who did not work were killed. In the spring of 1945, the Germans sent thousands of surviving prisoners on a death march to Dachau, where he survived the horrors of the final weeks of the war until the concentration camp was liberated in April. Basch was sent to an American field hospital where, after being in a coma for a month, he awoke on his 17th birthday. Searching for his family, he found one sister in Budapest: his father and one brother had disappeared, and his mother and a sister died at Auschwitz. He later discovered that another brother had also managed to survive and had made his way to Israel.

In 1947 Basch arrived penniless in the United States. He found work in Los Angeles and learned English at night school. Later he was joined by his sister and brother. Basch married and had three children, and became a successful businessman in the garment industry. He was one of the Holocaust survivors who told their stories in the 1998 Oscar-winning documentary, “The Last Days.” Bill Basch died in 2009 in Los Angeles at the age of 82.

Kailash Satyarthi

Wallenberg Medal 2002

One person can make a difference—in any culture, at any time. More than twenty years ago a young engineer gave up a lucrative career and dedicated himself to reclaiming the lives of South Asia’s most vulnerable population: the millions of children who are exploited and abused in a form of modern-day slavery.Kailash Satyarthi was challenged at an early age by the world’s economic inequities, and the grotesque wrongs they engender. On his first day of school when he was barely 6 years old, Satyarthi noticed a boy about his age on the steps outside the school with his father, cleaning and repairing shoes, and not entering the classroom like everyone else. He saw this every morning. It was a common sight in the central Indian town of Vidisha, but facing it daily left Satyarthi feeling humiliated, he said. One day Satyarthi gathered up the courage to ask the cobbler why it was so. The cobbler replied: “My father was a cobbler and my grandfather before him. We were born to work, and so was my son.”Satyarthi was left unsatisfied by that explanation, and by others offered by his parents, teacher and headmaster. “It was very difficult for me to understand,” he said. “I used to see that kid every day, and I was unable to solve the problem.” By the time he was 11, Satyarthi had begun urging other boys and girls to collect used textbooks and money to give to families who could not afford tuition for their children. It was the beginning of a life of activism.Satyarthi went on to study engineering, but did not last more than a year in that vocation after he graduated from college in Bhopal. It was 1980 and he had started a journal called The Struggle Shall Continue, when one day an old man staggered into the journal’s office with a horrifying story of children working in a brick factory, never seeing the light of day. “I decided right then to stop talking about the problem and go to the victims, and get them out of there,” he said. In the effort to save the children that day, Satyarthi and those with him were beaten by police, but the children eventually were released with the help of the courts. His original idea was daring and dangerous. He decided to mount raids on factories — factories frequently manned by armed guards — where children and often entire families were held captive as bonded workers.Typically bonding occurs when a desperate family borrows needed funds, often as little as thirty-five dollars, and is forced to hand over a child as surety until the funds can be repaid. Frequently the money can never be repaid and the child is sold and resold to different masters. Bonded laborers work in the diamond, stone-cutting and manufacturing industries and especially in carpet making where the children hand knit rugs that are sold in markets around the world, including the United States.Satyarthi has worked relentlessly to free bonded children, to rehabilitate them with vocational training and education and marshal the force of public opinion against child labor. His efforts have taken many different forms, some of them on an international scale. For example, in 1998 he organized the Global March Against Child Labor, bringing representatives from more than ten thousand non-governmental organizations together to pressure governments, manufacturers, and importers to stop illegal and unethical labor practices.Satyarthi’s courage and persistence have resulted in the liberation of more than 60,000 children in South Asia and beyond. From the journal office in Delhi, to founding the South Asian Coalition on Child Servitude, to leading the Global March Against Child Labor, Satyarthi said he has dedicated himself to reclaiming the lives of the world’s most vulnerable population: the millions of children who are exploited and abused in a form of modern-day slavery. “Children are sold by destitute parents into bonded labor,” Satyarthi said. “The children are then often re-sold into prostitution or, more recently, as forced organ donors.” He said he wants to give them a childhood, and to give them the tools they need to overcome poverty and abuse through education and validation as human beings.Satyarthi continues to risk his life every day, and has received constant death threats from those opposed to his work. The threats are dire, for two of Satyarthi’s colleagues have been murdered and in 2004 Satyarthi was violently assaulted during his group’s effort to free Nepalese girls from forced labor as circus workers. Satyarthi wrote to supporters afterward, “I have always taken such incidents as a big challenge. The fight against human slavery and trafficking is no mere charity. It is a tireless struggle….They can kill our body, but we will emerge again like the phoenix.”

Marcel Marceau

Wallenberg Medal 2001

The internationally celebrated mime Marcel Marceau became the eleventh recipient of the Wallenberg Medal on April 30, 2001. Rackham Auditorium was standing-room-only that night.“This year the person chosen to be the Wallenberg Medalist is unlike all previous medalists in that he is famous all over the world,” said University of Michigan professor emerita Irene Butter in her introduction. “Yet he is not widely known for his humanitarianism and acts of courage, for which we honor him tonight.”Many who learned that Marceau was going to receive the Wallenberg Medal had two questions, said Butter. First, could a mime give a lecture? Second, what had he done to deserve the honor? Butter answered the first question by quoting Marceau: “Never get a mime talking, because he won’t stop.” As for the second question, continued Butter, “Unknown to most, Marcel Marceau experienced early in his life some of the tragedies of World War II. However, until quite recently, he did not speak about those war experiences—experiences which prompted him to risk his life on behalf of others.”Marceau’s silence is not surprising, according to Butter, herself a Holocaust survivor. “Many, if not most, survivors of the Holocaust were not able to speak about it for nearly half a century,” she said. “Marcel Marceau is known as the Master of Silence—it may have been particularly difficult for him to break the silence about this tragic period in his life.” Despite his public reticence about his early life, however, Marceau has spent more than half a lifetime trying to express the tragic moment through his art.In 1939 the Jews of Strasbourg, France, where Marceau’s family lived, were given two hours to pack their belongings for transport to the southwest of France. Marcel, who was fifteen at that time, fled with his older brother Alain to Limoges, where they joined the underground. Marcel changed the ages on the identity cards of scores of French youths, both Jews and Gentiles. He wanted to make them appear to be too young to be sent away to labor camps or, in the case of the non-Jewish children, to be sent to work in German factories for the German army. Marceau also adopted different poses, including that of a Boy Scout leader, when he put his life at risk to smuggle Jewish children and the children of underground members across the border into Switzerland.In his lecture, he said that he had relied on his acting skills to do this. In 1944, while a member of the Resistance in Paris, Marceau was hidden by a cousin. He was convinced that if Marceau survived the war, he would make an important contribution to the theater. Marceau’s father,a butcher, died in Auschwitz. “If I cry for my father,” said Marceau, “I have to cry for the millions of people who died. “I have to bring hope to people,” Marceau remembered thinking after the war. He had planned to become an artist, but instead decided that he wanted to “make theater without speaking.” He began to study under the great master of mime Etienne Decroux. In 1947 Marceau created Bip, the clown in the striped jersey and battered opera hat, who has become his alter ego.In his lecture, Marceau spoke of his piece “Bip Remembers,” where Bip goes out of character for the first time, to become “humanity.” Wave after wave of people are killed, until the last wave witnesses enlightenment. “Pray that this millennium will be less cruel than the twentieth century,” said Marceau. Marcel Marceau closed his talk with his gift of mime. Dressed in mufti, he returned to his world of silence, drawing the audience along and ending the evening with the vision of the flight of a butterfly winging to freedom.Marcel Marceau died in September, 2007 in France.

Wallenberg Medal Laureates (2000 ~ 1990)

Nina Lagergren

Wallenberg Medal 2000

The tenth Wallenberg Medal was presented to Nina Lagergren, Raoul Wallenberg’s sister, in memory of Raoul. Lagergren came to Ann Arbor in October 2000 to accept the medal and to deliver the Wallenberg Lecture. It was her first visit to the city and to the University of Michigan, which had nurtured her brother for four years in the 1930s. She was accompanied by two of her daughters, Mi Wernstedt and Nane Annan.A Swedish lawyer and artist, Annan is married to United Nations Secretary-General Kofi Annan. She introduced her mother that evening. “Sweden was spared the ravages of war, but our family suffered the loss of a brother not returning from the mission he had been sent to achieve,” Annan said. “My mother has taken on the courageous struggle to find Raoul,” she continued. “For me, it’s of special importance also because I am the little girl, born in October 1944, to whom Raoul, in his last letter to his mother, sends ‘lots of kisses.’”Lagergren began by expressing her gratitude to the people in Ann Arbor who have kept Raoul Wallenberg’s Michigan legacy alive. Earlier that day she and her daughters had explored the campus and the city. Their tour included retracing Raoul’s path from his apartment on Madison Street to Lorch Hall, which in the 1930s housed the architecture school where he studied.“It has never happened to me before—this intimate relationship with people who have worked to keep Raoul’s deeds in front of everyone,” said Lagergren. “It is a wonderful help for us in Sweden for our cause.”Nane Annan mentioned in her introduction that her mother was not used to taking center stage. But when Lagergren’s parents died in 1979, she and her brother Guy von Dardel had no choice but to take over the mission to find Raoul. Nearing eighty at the time of her Ann Arbor visit, Lagergren continues to reach out to youth with the message of Raoul Wallenberg. She told listeners in Ann Arbor that a turning point occurred twenty years ago, when, encouraged by détente with the Soviet Union, a committee to find Raoul Wallenberg formed in Washington, D.C. “All of a sudden publicity about Raoul was brought to the world, and there was a snowball effect,” she said.Because filmmakers and biographers wanted information about Wallenberg, Lagergren began to research her brother’s story. With affection, she detailed what she had discovered, beginning with Wallenberg’s birth after the tragic death of his father. “From the very start he was the joy of the family,” she recalled. “Raoul went to America when I was only ten years old,” remembered Lagergren. “He was the sweetest of brothers, and I adored him.” Lagergren said that she was a girl of fifteen when the dashing Raoul came back to Sweden from America. Soon he left again to work in South Africa and Palestine. When he returned to Sweden, Lagergren recalled going with him to the U.S. embassy in Stockholm to see the movie “Pimpernel” Smith, about a professor helping his Jewish friends escape Nazi Germany. “This is something I would like to do,” Raoul told his sister. “Nothing could stop him,” Lagergren said, recalling Raoul’s decision to go to Budapest in 1944 to try to save the Jews who had not yet been deported to death camps. He demanded a free hand with no diplomatic roadblocks, she said. The family knew of his dangerous mission but always expected that he would return.Nina Lagergren faults the Swedish government for its timidity with her brother’s Soviet captors. She noted that Swiss diplomats were also taken into the gulag. But the Swiss government acted immediately to secure their return. The mystery of her beloved brother’s disappearance has left Lagergren frustrated but determined. “Raoul was the center of our lives. Here we are—we still don’t know. The Russians haven’t given us the truth. We fought for fifty-five years to get him back, and now we are fighting for the truth.”

John Lewis

Wallenberg Medal 1999

“If anyone had told me that one day I would be standing here receiving this great honor, this great medal…as a member of Congress, I would have said, ‘You’re crazy!’” John Lewis, ninth Wallenberg Medalist, told his audience at Rackham Auditorium in January 2000.The famed civil rights activist was recalling his hardscrabble youth in rural Alabama. One of ten children of religiously devout sharecroppers, he attended segregated schools and was once refused a library card from the Pike County library. In his talk, Lewis—whose powerful voice can be redolent of his ministerial training—recalled, “I was told by the librarian that the library was for whites and not for coloreds.”Lewis came from a different world than did Raoul Wallenberg, the scion of Swedish aristocrats. “What are the parallels that can be drawn between these two remarkable figures?” asked University of Michigan professor emerita Irene Butter, in her introduction. “Both Congressman Lewis and Raoul Wallenberg had a strong sense of mission,” she said. “A mission that was pursued at all costs…even under seemingly hopeless circumstances.” Butter pointed out that both Wallenberg and Lewis were young men when they put their lives at risk to oppose, respectively, the evils of Hitler’s anti-Semitism and the inbred racism of America’s Deep South. Then-University of Michigan President Lee Bollinger, who followed Butter, said that during the civil rights battles Lewis “was arrested more than forty times, and was physically attacked and seriously injured on several occasions.”One such occasion was the famous Selma march on March 7, 1965. In his lecture, Lewis recreated the terrible day that marchers set off from Selma, Alabama, to a planned protest in Montgomery, the state capital. The marchers didn’t get far. Crossing a bridge, they froze when they saw what Lewis called “a sea” of blue-helmeted, blue-uniformed Alabama state troopers. An officer with a bullhorn bellowed, “This is an unlawful march.” Then hundreds of state troopers, Lewis continued, “came toward us, beating us with their nightsticks, bullhorns, whips….” One trooper smashed a billy club against Lewis’ head. “To this day,” the Congressman said, “I don’t know how I made it back across the bridge.” On the evening after the aborted march an injured Lewis told a crowd, “I don’t know how President Johnson can send troops to Vietnam, but not send troops to Selma to protect people whose only desire is to register to vote!” A week later, Lyndon Johnson made his most impassioned speech to date on the civil rights movement. And four months later, Lewis told the U-M audience, “the Voting Rights Act was passed and signed into law.”Just twenty-five at the time of the signing, Lewis was nonetheless a veteran of the civil rights movement. As a college freshman at the all-black American Baptist Theological Seminary in Nashville, Tennessee, he had not, to his parents’ dismay, concentrated on his studies. Instead, he joined a group of students organizing sit-ins at department store lunch counters closed to blacks. In 1960, he helped organize the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee (SNCC), the catalyst for much of that era’s civil rights activism. Unlike Raoul Wallenberg, Lewis lived to see the other side of the struggle. The Civil Rights Act of 1964 and the Fair Housing Act of 1968, as well as the Voting Rights Act, brought millions of marginalized blacks into full participation in the American system. Lewis settled in Atlanta, served on the city council, and was first elected to Congress, as a Democrat, in 1986. Today Chief Deputy Democratic Whip in the U.S. House, Lewis continues to fight for the ideals of his youth. In 1998, he successfully led opposition to a congressional amendment that would have prohibited federal funding to universities with affirmative action programs.That same year, Lewis also won another, more personal victory. The Pike County library that shunned him as a child invited him back to do a book signing—and finally issued him a library card. “It says something,” Lewis told his audience in Ann Arbor, “about the distance we have come.”

Simcha Rotem

Wallenberg Medal 1997

As he walks through his Jerusalem neighborhood overlooking the Old City, Simcha “Kazik” Rotem points out to a visitor that these houses were under fire during the 1967 Six-Day War. He used the Polish Gentile name Kazik in the Warsaw ghetto in 1943 as part of a disguise. There is no fear in Kazik’s voice as he speaks of the war in Jerusalem. But then, why would a man who survived the hell of the Warsaw ghetto ever again feel fear?Kazik is one of the few surviving Warsaw ghetto fighters. How did he survive when so many others did not? To his anguish, it was a question many asked when he arrived in British-occupied Palestine in 1946. To avoid the questions—and the memories—he learned not to speak about his past.Now, late in his life, Kazik has spoken. As he said in his 1997 Wallenberg Lecture in Ann Arbor, “The thought of fighting in the ghetto was totally unrealistic and contrary to everything the word ‘ghetto’ represents.” But Kazik and his brave colleagues did decide to fight, even though fighting the Germans meant almost certain death. After the German invasion of Poland, Jews in and around Warsaw were gathered up and forced to live in an area that made up only about 3 percent of the city. There were more than 500,000 people living in squalor in the Warsaw ghetto. The first massive deportation began in 1942. Spies from the ghetto told young resistance fighters like Kazik that the trains traveling from the ghetto to the camps were leaving the camps empty. Kazik and other Zionist youth group members decided to revolt.The Warsaw Ghetto Uprising began in April 1943. With mines, grenades, pistols and Molotov cocktails, Kazik and the other Jewish fighters killed a number of Germans who came to attack the stronghold within the ghetto. Then the Germans attacked from outside the ghetto, burning down all the shelters and equipment the fighters had left. Kazik and some other surviving fighters tunneled outside the ghetto walls. However, that was not the end. “Unfortunately, we had no one to rely on except ourselves,” Kazik recounts in his book, Memoirs of a Warsaw Ghetto Fighter. “In my innocence I had thought that by getting out of the ghetto I had accomplished the essence of my mission…but we were still at the very beginning.”He was at the beginning because of incredible selflessness. Kazik could have chosen to save himself, but he and the others who escaped decided to return to the ghetto through the sewers to save the remaining fighters. Crawling through the stench, Kazik reached the ghetto but found only ruins. “My life passed before my eyes, like a film, at a frantic pace,” he continued. “I saw myself fall in battle as the last Jew in the Warsaw ghetto. I had begun to lose all thoughts of survival. With a sudden effort, I wrenched myself free of thoughts of suicide and decided to return to the sewers.” There, Kazik encountered more Jewish fighters who had escaped. Although some of the fighters survived, the Nazis had killed most of them as they emerged from hiding.The handful of remaining ghetto fighters was not yet safe. Still disguised as a Polish Gentile, and always wary of traitors and informers, Kazik continued to live in and around Warsaw, even escaping, through wit and luck, several detentions by the Gestapo. After Warsaw was liberated in January 1945, he learned of a miracle—his parents were still alive. Although his brother and one of his sisters had been killed, the family was among the few to emerge with even remnants intact. Kazik finally realized his boyhood dream of living in Israel by joining the clandestine Aliyah Bet immigration in 1946.Kazik’s heroic deeds are shadowed by tormenting memories of the ghetto. He told a rapt Ann Arbor audience, “One night I was on patrol in the nearly completely destroyed ghetto. I came upon a heap of human bodies. There was a sound of crying, and there was a dead mother still holding her baby. I stopped for a moment, then went on. The Germans had succeeded not only in annihilating the Jews, they had also robbed me of my humanity.”

View More

Marion Pritchard

Wallenberg Medal 1996

Marion Pritchard protected the lives of 150 Dutch Jews—most of them children—during World War II, using whatever means were at hand. “By 1945 I had lied, stolen, cheated, deceived and even killed,” she told the audience assembled in Rackham Auditorium for the seventh Wallenberg Lecture in October 1996. She emphasized that she did not work alone, but with many collaborators, often Jews, who were taking a bigger risk than the Gentiles because they were treated more harshly if they were caught.Pritchard was forced to kill a man while hiding three Jewish children. When a Dutch policeman brought three Nazi officers to her house, the children, hidden under the floorboards in the living room, escaped detection. “But an hour later, after I had let the children out, because the youngest, two-month-old Erica, was crying, the policeman came back alone,” she recalled. “I felt I had no choice but to shoot him.” In her lecture, Pritchard focused on her personal experiences with Jewish rescuers. She spoke of her neighbor and friend Karel Poons, a Jewish ballet dancer, who was determined to assist in the rescue effort of as many Jews as possible. After Pritchard killed the policeman, Poons quickly came to her aid. Pritchard knew what his fate would be if he was caught trying to save Jews. “In spite of the curfew, he walked to the village and talked with the baker, who agreed to come get the body.”Pritchard also admits to being a kidnapper. Lientje Brilleslijper, a talented Jewish dancer and singer, was in hiding with her husband, her two-year-old daughter Kathinka, and other members of her family. When their house was surrounded by the SS, Lientje pretended to have a fit, hoping that after the Nazis arrested her they would not trust her with her daughter. The ruse worked—Kathinka was taken to the home of a local doctor. The next day, the SS tried to get Lientje to talk by threatening to bring in Kathinka and torture her. A friend alerted Pritchard, asking her to steal the little girl before the Germans did. Once again, Karel Poons insisted on helping out. He and Pritchard went to the home where Kathinka was being held. While Poons distracted the doctor and the guard at the front door, Pritchard ran in the back door. “Fortunately, Tinka was already dressed,” recalled Pritchard. “I grabbed her, ran down the stairs, put her on the back of my bike and pedaled off.”Pritchard said she learned that people can’t be tidily divided into victims, rescuers and bystanders. For example, some bystanders helped, she says, by not telling on people in hiding. Others might not have been imaginative or bold, but they helped if asked to do so. A farmer knew that she was hiding children, although they never spoke about it. Every day he left her extra milk.Even German soldiers came to Pritchard’s aid near the end of the war. Pritchard bicycled north in search of food, loaded down with family silver. She successfully bartered with some farmers. On her way back home German soldiers stopped her. Exhausted and frustrated, Pritchard lost her temper. She told them what she thought of the war and of the way the Jews were being treated. Others tried to shut her up, knowing that people had been killed for lesser offenses. But Pritchard couldn’t stop. She was detained overnight, and the next morning two soldiers came to her. She expected to be killed. Instead they put her in a truck, along with her bike and the food she had bartered for, and drove her to safety.Today Pritchard lives in a farmhouse in rural Vermont. She and her late husband, Tony, raised three sons, who all work in the helping professions. Throughout her life Marion Pritchard has continued to be a formidable advocate for children, first as a social worker and then as a practicing psychoanalyst. Erica and Kathinka survived the war and went on to lead fulfilling lives. Pritchard is still in touch with both of them today.Israel made Marion Pritchard an honorary citizen in 1991. At Yad Vashem, Israel’s memorial to the Holocaust, she is among those designated as Righteous Gentiles.

Per Anger

Wallenberg Medal 1995

“Never has a man succeeded in modern times to save that many people in such a short time as Raoul Wallenberg did.”-Per AngerPer Anger worked side-by-side with Raoul Wallenberg to save Jews in Budapest from the Holocaust. In 1944 and early 1945, he assisted Wallenberg, witnessing his extraordinary actions first-hand. After the Soviet Army seized Wallenberg in January 1945, Anger dedicated much of his life to discovering what happened to his colleague and friend.By the time Raoul Wallenberg arrived on his mission in July 1944, Per Anger and his small staff at the Swedish embassy in Budapest had already saved 700 Jewish lives. Anger had been asked for help by a Hungarian Jewish businessman, Hugo Wohl, when he and his family were facing deportation to death camps. Diplomats from Switzerland, Spain, and Portugal were distributing passports, emigration documents and other papers to protect Jews under the threat of death. Anger recalled desperately thinking that something more needed to be done. He fabricated invalid but official-looking Swedish passports to grant Wohl and other Jews immunity from deportation. When Wallenberg arrived at the embassy, remembers Anger, “he looked at my visas and said, ‘Good, but I can do it better.’” Together Wallenberg and Anger designed the Schutz-Pass, a more elaborate and official-looking version of Anger’s documents.Anger helped Wallenberg use American funds to buy buildings to shelter Jews who held the forged documents that Wallenberg and his network were distributing across the city, and to place these crowded structures, as property owned by the Swedish embassy, under diplomatic privilege and protection of the Swedish government. Anger recalled Wallenberg’s frequent trips to the railway station to save people being loaded onto trains for deportation to death camps. He accompanied Wallenberg on rescue missions to intercept death marches across the Hungarian-Austrian border. “He always found a solution, invented a new way of saving people.” He would say to startled Jews on their way to Auschwitz, “Oh, you remember—the Hungarians confiscated your passports,” related Anger. “They ‘remembered’, and we took fifty people away.”In Sweden after the war, Anger became head of a special commission to look into the disappearance of Raoul Wallenberg. He resigned in 1951, frustrated by the lack of cooperation from the Swedish government to aggressively pursue the question of Wallenberg’s fate in Soviet hands. For the rest of his career Anger pursued any leads that came up. In 1979, when he retired after forty years of distinguished diplomatic service to Sweden, he devoted all his efforts to discovering the truth behind Wallenberg’s disappearance. He wrote a memoir, With Raoul Wallenberg in Budapest: Memories of the War Years in Hungary (Holocaust Library: 1996)In 1982, Per Anger was honored as one of the “Righteous Among the Nations” by Yad Vashem, Israel’s memorial to Jewish victims of the Holocaust, for risks he took saving the lives of the Jews of Budapest. He was awarded honorary Israeli citizenship in 2000, and in 2004 Sweden established the Per Anger Prize to promote initiatives supporting human rights and democracy. Per Anger died in August 2002 at the age of 88.

Miep Gies

Wallenberg Medal 1994

Gies sheltered Anne Frank and her family from the Nazis in Amsterdam during World War II. She came to international attention after the posthumous publication of Frank’s diary.While millions of people all over the world know about Anne Frank, far fewer are aware of Miep Gies, the woman who sustained Frank and her family in hiding during World War II. The humanitarian actions of Gies more than fifty years ago in Nazi-occupied Amsterdam have had a special and enduring impact. Were it not for Miep Gies, the world would never have met Anne Frank.Moral courage and modesty are at the heart of Gies’ character. For more than two years, she risked her own life daily to illegally protect and care for the Franks and four of their friends hiding from the Nazis in an attic. She insists that she is not a hero. “I myself am just an ordinary woman. I simply had no choice,” she told a standing-room-only audience during the fifth Wallenberg Lecture, in Rackham Auditorium, on October 11, 1994. Gies knew of many other Dutch people who sheltered or helped Jews during the war. Her name has become known, she said, only “because I had an Anne.” Gies assigned the title of hero to the eight souls who hid in the attic. “They were the brave people,” she said.Gies was born in 1909 in Vienna. At the age of eleven, recovering from tuberculosis and suffering from poor nutrition, she was sent to live with a family in Amsterdam. Her Dutch foster parents already had five children. Despite their modest income they welcomed her into their family, sharing with her everything they had. The love and compassion she received from her new family impressed Gies profoundly and she decided to make Holland her permanent home. She was influenced by the values of her foster family. Later, when her employer, Otto Frank, asked her if she was prepared to take responsibility for his family in hiding, she answered “yes” without hesitation. “It is our human duty to help those who are in trouble,” Gies said in Ann Arbor. “I could foresee many, many sleepless nights and a miserable life if I had refused to help the Franks. Yes, I have wept countless times when I thought of my dear friends. But still, I am happy that these are not tears of remorse for refusing to assist those in trouble.”Gies provided the Franks with food, clothing and books during their years in hiding—to the best of her ability she addressed all of their daily material needs. She was also one of the few links with the outside world for the Franks and their friends, and she was their main source of hope and cheer. She knowingly faced great personal risk, acting out of integrity and in consonance with her own internal values. Gies tried to rescue the Frank family after they were taken from the attic, attempting to bribe the Austrian SS officer who had arrested them. She even went to Nazi headquarters to negotiate a deal, fully aware that this bold move could cost her her life.After the Franks were betrayed and arrested, Gies’ work continued. She climbed the attic stairs one more time to retrieve Anne’s writings, finding them scattered on the floor. Gies quickly gathered up the notebooks and kept them for Anne’s expected return after the war. When she learned of Anne’s death in Bergen-Belsen, Gies gave Otto Frank his daughter’s notebooks. Ever since, Miep Gies has mourned the cruel fate of her friends in the attic. “Every year on the fourth of August, I close the curtains of my home and do not answer the doorbell or the telephone,” she said. “It is the day that my Jewish friends were taken away to the death camps. I have never overcome that shock.”Miep Gies’ message in her Wallenberg Lecture was one of hope: “I feel strongly that we should not wait for our political leaders to make this world a better place.” Miep Gies has been honored around the world for her moral courage. In Israel the Yad Vashem Memorial pays tribute to her as a Righteous Gentile.Miep Gies died in January, 2010, in the Netherlands.

Tenzin Gyatso

Wallenberg Medal 1994

Nobel laureate, spiritual leader and head of the Tibetan government in exile, His Holiness is an internationally honored proponent of nonviolence, human rights and peace.His Holiness Tenzin Gyatso, Fourteenth Dalai Lama and spiritual and secular leader of the Tibetan people, is revered by Tibetans and Buddhists worldwide. Since 1959 he has lived in exile in India and struggled to resolve his country’s political problems peacefully, while protecting and enhancing the Tibetan culture and language. In 1989 he was awarded the Nobel Peace Prize.On April 21, 1994, despite the busy exam week, many students and faculty mingled with a crowd of over 10,000 entering Crisler Arena for the fourth Wallenberg Lecture, delivered by the Dalai Lama. He spoke to his Ann Arbor audience of the goal for humanity in the twenty-first century, which is “to build a happier world.” However, for this dream to be fulfilled, “efforts must come from the present generation, especially young people, with confidence and hope and activation of our potential.”The Dalai Lama also spoke about the need for individual compassion, courage and confidence. The focus must be on individuals, rather than on political leaders, he said. “We must work with individual people—then, maybe, the leaders will follow.” He insists that evil is not intrinsic and that no situation is beyond hope. “It is important to not see one’s oppressors as nonhuman—even in the face of inhumane treatment.”The Dalai Lama remains firmly committed to nonviolence. “It is important to act out of a sense of personal responsibility, to act quietly, behind the scenes,” he said. He has this in common with Raoul Wallenberg, who saved the lives of Budapest’s Jews by using psychological cunning rather than weapons.“While you are gaining an education, be a nice person, be a compassionate person, be yourself…. The brain and the heart must go together,” he told the students in the audience. “Sometimes in universities not enough attention is paid to the heart. I have the impression that the moral sense is underdeveloped,” he said to enthusiastic applause. “Knowledge is an instrument,” he continued. “Whether [it is] used constructively or destructively depends on spirituality, human feeling and affection.”Raoul Wallenberg was a good student in Ann Arbor. But his friends did not remark on his academic accomplishments when news of his humanitarian deeds in Budapest reached the United States after the war. Instead, they said they were not surprised, remembering his complete lack of snobbishness and genuine concern for others— his large heart. University of Michigan student Raoul Wallenberg exemplified the Dalai Lama’s ideal student.The Dalai Lama recalled his visit to the United States Holocaust Memorial Museum in Washington, D.C., which displays the hatred and violence of human beings who caused “unmeasurable, unthinkable suffering.” He spoke of the area in the museum that portrays individuals like Raoul Wallenberg “who utilized positive human potential, with compassion, which shows what humanity can achieve.“If we just say a few words to remember past heroes, that is not a genuine tribute,” the Dalai Lama said as he concluded his speech. He told the students that the best way to honor great humanitarian heroes like Raoul Wallenberg “is to implement with self-confidence and a sense of involvement the ideas of our previous heroes.”The Dalai Lama made a deep impression on those who met him during his short visit to Ann Arbor. All were touched and warmed by his humbleness, self-effacing humor and infectious laughter. He treated all people he encountered with unassuming informality, whether they were security personnel or the president of the university, grasping the hands of everyone within reach.“We’ve all become cynical about religious leaders, and we’re often disappointed by important people,” said University of Michigan professor of Buddhist and Tibetan studies Donald Lopez of the Dalai Lama’s presence in Ann Arbor. But people “recognized his authenticity,” said Lopez. “His visit was really an extraordinary moment for the U-M.”The University’s Wallenberg Medal was the second honor accorded to the Dalai Lama in memory of Raoul Wallenberg. In 1989 U.S. Representative Tom Lantos presented him with the Raoul Wallenberg Congressional Human Rights Award.

Helen Suzman

Wallenberg Medal 1992